Excerpt from Video Cultures in India: The Analog Era

Ishita Tiwary

May

2023

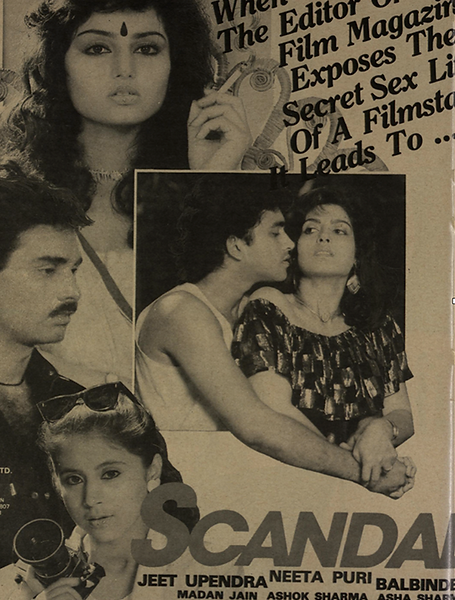

Promotional poster for the video film Scandal

In their Nov 1989 issue, TV and Video World proclaimed the 1980s to be the ‘Video Decade.’[1] In its cover blurb, the magazine noted that “the 80s witnessed the emergence of video as an exciting home entertainment medium” and that video has “transformed India’s social landscape.”[2] Retrospectively describing the arrival of video in India, the magazine wrote, “the VCR’s trickled in past befuddled custom officers, as part of the jetset baggage. And custom officers scratched everywhere but their brains with their ever-ready high duty pencils in trying to classify those rectangular boxes with their funny-looking cassettes. Puzzled, they were. You couldn’t blame them. The first contact with VCRs evoked such responses.”[3] The story also highlighted the new technical features that video wrought upon its arrival. Taking note of its bulky size, the feature referred to the heavy-duty paid for this large item. Further, “they came with a few frills: quick rewind and forward, recording timer switch, camera recording facility, pause, picture sharpness, etc.”[4] The blurb here illustrates the peculiar affordances of video and judging by the responses of the customs officers an apparatus that disrupted the media landscape.

Fast forward almost thirty years, I find myself in a small office space in the Information and Broadcasting Ministry on a hot June day in Delhi. It is the early days of my archival work, and I am fielding questions from research office bureaucrats as to what exactly I was doing there. Their queries frustrated me, as I was struggling to find information on 80s video practices in India. The dominant narrative in popular discourse in India, at the time, was around video piracy. Moreover, video studies had become an established field in North America and Europe, the debates to which I felt my research would not be able to make a substantial contribution given the consistent dead ends during the early stages of my archival work. As I carefully turned a fragile page of a leather-bound dusty volume, the term ‘video film’ caught my eye. Intrigued, I started keeping my eye out for this term. While chasing down its definition in the archive, I discovered that it not only meant mainstream films converted to video post release, but also films shot, edited and distributed on video. Excited by this discovery, I started reading the archive more carefully, paying close attention to the margins, on the lookout for stories and forms around video that captured the affective force field of the 80s. The first thing that struck me was the shrill moral panic and paranoia triggered by the arrival of video. From anxieties about piracy to fear of pornography and violence, video resembled a plague that supposedly needed monitoring and regulation. However, alongside this paranoia, another narrative emerged. I discovered letters to the editors written by readers from small towns who recalled how video had exposed them to a wide variety of films that were not often released in small towns. This sense of excitement and possibility was later echoed by the videographers, editors and cameramen whom I later interviewed during my research. In contrast to the expensive technology of celluloid, video’s portability and affordability encouraged many enthusiasts to take up distribution via parlours and libraries or produce content through films made on video.

These anecdotes, separated by time and space, speak to the importance of video cultures and how their short lives have made them a difficult object to trace and study. I uncovered narratives about the emergence and existence of new spaces of circulation engendered by analog video: the video library where one can rent a video cassette, the illicit video parlour, informal spaces screening pirated videos, and the neighbourhood cable business that could broadcast videos. It led to different modes of professionalization, self-learnt through manuals or recently graduated from film schools such as the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) or Anwar Jamal Kidwai Mass Communication Research Centre (AJK MCRC), Jamia Millia Islamia. In turn, the new spaces and new types of professionals led to the emergence of new forms such as wedding videos, religious videos, video films and video news magazines. These new infrastructures in turn led to formation of new forms such as the wedding video, video films, video magazines and the religious video. Video disrupted the way one thought about the ways media functioned in the spaces of circulation, the content made on video, and the people involved in creating and circulating this content.

Within the relatively long history of cinema in India, the era of analog video lasted for just about a decade and a half from the early 1980s through to the late 1990s. In this brief period, video redefined everything we had known about cinema. It was as if the video revolution triggered a rebirth of cinema. Video’s history, therefore, has become inseparable from our personal and collective experiences of cinema. The video decade brought film into domestic spaces, ushering a shift in the perceptual regime of the spectator with media now available at home. Video displaced cinema both spatially and temporally. If film watching had been strictly regulated by the state, video moved cinema into other spaces: into video parlours and the living room. Video also changed our temporal control over cinema; the ability to fast forward, rewind, record and pause changed cinephilia as spectators were now able to determine their own experience of film.

This book, thus, on one level narrates a story, a partial history of analog video infrastructures in India in the 80s and its affordances and affective charge. It is about video modernities that get engendered through these new formations and participate in the social and political events of that period. Secondly, is also about method. How to uncover media objects and their histories when they are not privileged by formal archives? How to track and view media technologies that have become obsolescent? Third, this work is about media continuities, how video histories are an important inflection point on current debates on new and digital media on a macro level, and in understanding the relationship between the Indian mediascape and society on a micro level. Finally, the book offers an alternative way to think about video histories, its uses and aesthetics from the vantage point of the global south, and how the writing of these histories contributes to a different way of thinking about modes of knowledge production.

In 1982, analog video arrived in India when the national television network, Doordarshan, aired the Asiad Games, which was seen as a way to project the image of a modern India to an international audience in the post-Emergency era. the advent of video created a revolution, of sorts, the audience withdrew from the theatres and moved to the private space of their living rooms. The video revolution rode on the growth of television in the 80s. From 18 transmitters in the early 80s, the numbers grew to 175 during the late 80s. Individually owned television sets grew to almost 7 million by the late 80s. [5] Television ownership increased alongside a rapidly expanding audio and video cassette market which existed almost entirely in the pirate economy, and spaces like video libraries. Video parlours and video theatres sprung up along with restaurants, buses and shops which began installing video equipment (Sundaram, 2010). These new sites were the spaces where viewers were accessing as-yet-unreleased Hollywood Films, the latest releases from Hindi and regional cinema, as well as pornography.

Informal circuits were crucial to the narrative of analog video in India. Spaces of distribution such as video libraries, video theatres and video parlours caused much anxiety, and the law was used as an instrument of containment. Legal judgments on the regulation of these spaces and the discourses employed in popular print culture offer an interesting account of analog video’s peculiar place in the complex regime of legal transactions. Video became a cause of both moral and economic anxiety.[6] Moral concerns centred on the widespread circulation of pornography and the act of piracy. The menace of video (Suresh, 2007, pp 109) was seen as the cause for a cancerous spread of adult films (ibid). There were numerous reports of raids at video parlours by the police to confiscate illegal screenings of pornographic films with teenage boys in the audience. The act of piracy was seen as dangerous and a reflection of the ‘crisis of character’ that had overtaken the nation.[7] An editorial in Screen India compared pirates to smugglers and thieves, provocatively stating that allowing pirates to operate was akin to smugglers demanding safeguards for themselves and thieves demanding rights to other men’s property.

Drawing from these academic and archival debates, perhaps one can posit that the arrival of analog video was a force of disruption in its affordances. In its short life, video threatened cinema’s status as the dominant medium, highlighted in the economic and moral panic generated by the medium’s arrival and the string of legal regulations and judgements that sought to define video as distinct from cinema. The receding of cinema’s dominant status, evident in dwindling box office receipts, provided a diverse set of entrepreneurs with an opportunity to capitalize on the new medium. The forms generated by video retained connections with older forms such as cinema, photography, advertisement, tabloid journalism, print journalism, broadcast news, pamphlets and audio cassette culture. The medium of video demands itself to be investigated in order to tease out connections, parallels, and differences between the analog and the digital.

I have, therefore, situated video as a medium – the physical material such as Videotape and VCRs and formats such as U-matic, Betamax and VHS – and an infrastructure that includes the production, circulation and distribution practices that utilized video. Such an understanding helped me to track production and reception practices, their relationship to the prevailing socio-cultural context of the time and the emergence of a distinct ‘video aesthetic’ located across a range of video productions. Thus, I have attempted to go beyond piracy to locate video as a medium, a cultural force, an institutional development and an aesthetic configuration. Media studies has taken a distinct infrastructural turn in recent times, and I draw upon those debates to think about analog video infrastructurally. In the book, I look at video aesthetics and how it interacts with the everyday, the pro filmic, the political and religious life. While a material and medium based approach is crucial to this conversation, the infrastructural turn provides a methodological impetus to study this relationship. I use Brian Larkin’s (2013) approach to frame video as infrastructure, locating its operations as a technological moment that dovetailed with prevailing socio-political and cultural changes. I encountered a number of practitioners of this period to understand its possibilities and its limitations in constructing new forms of video imaginaries. [8]

Video became a key media infrastructural moment in post independent India’s history. “Media has become the infrastructural condition of living, rather than existing as distinct, regulated sites like the cinema theatre, or as celluloid” says Ravi Sundaram (2015) in his reflections on the links between post-colonial media infrastructures of the late 1980s and the contemporary. In the post cassette boom of the 1980s, infrastructures became central to media circulation, primarily through the entanglement of “people, objects, knowledges, and technologies” (ibid). I want to latch on to Sundaram’s understanding of media as an ‘infrastructural condition of living.’ The forms of video discussed in this book are not self-contained or limited to analog video but continue to have long afterlives. For instance, with the advent of the digital, the wedding video is thriving and now shoots using drone technology. The video news magazine migrated to television and is the antecedent to what is now one of the largest news networks in India-TV Today as well as the new media platform- Newslaundry. The videos of Rajneesh continue to remain popular through their circulation on YouTube and as archival material in documentaries such as Wild Wild Country. The use of media by the Rajneeshees set a template for other Godmen.

I have structured this book on the basis of key thematic areas and case studies. The mode is of historical reconstruction, where each chapter opens with a contemporary example and ploughs backwards in time to shed light on these video forms. Delhi has been the field site for my chapter on the wedding video; in my exploration of video-films, I have focused solely on productions by Hiba Films. For video-magazines, I have looked specifically at Newstrack (a current affairs news magazine) as my case study. Finally, for the religious video chapter, I have analyzed the video pravachanas of the Rajneesh (currently known as Osho) commune. Through these specific case studies, I have tried to concentrate on the specific configurations of video rather than present large-scale generalizations.

Video Cultures in India draws on oral histories, discarded tapes, and forgotten archives to unravel the history of analog video in India alongside a broad narrative of the cultural history of the country from the 1980s to the early 1990s.

Footnotes

[1] TV and Video World, Vol 6, Issue 11, Nov 1989, Cover Page. Return to text.

[2] ibid, pp 29. Return to text.

[3] ibid, pp 31. Return to text.

[4] ibid. Return to text.

[5] ibid. Return to text.

[6] Lucas Hilderbrand (2009) has pointed out that in the US, the arrival of home video created a panic amongst studio executives who feared the film industry would be devastated by revenue losses as audiences started leaving the cinema theatres to watch movies at home. The studios waged litigation wars against home video, with the most famous of them being the Sony vs Universal case (1976-84).20 The US experiences resonates with some of what was happening in India. Return to text.

[7] R.K. Sharma, ‘Ending Piracy: Not by legislation alone’, Screen India, June 29, 1984. Return to text.

[8] Brian Larkin defines infrastructure as a material form that facilitates the flow of goods, people and ideas, shapes networks and provides the architecture necessary for circulation. Infrastructures, he argues, go beyond their technical functions to operate as ‘aesthetic vehicles oriented to addressees’ (pp. 329). Infrastructures enable the movement of desire and affect and therefore remain critical in the constitution of subjects. Return to text.

Ishita Tiwary's research interests include video cultures, media infrastructures, migration, contraband media practices, and media aesthetics. She has published essays in Bioscope: South Asian Screen Studies, Post Script: Essays in Film and Humanities, Culture Machine, MARG: Journal of Indian Art, and in edited collections on topics of media piracy, video histories, and streaming platforms.

She is currently working on two projects. The first is her book monograph that traces the history of analog video cultures in India through an infrastructural lens. The second research project tracks the migration of pirated media objects and people from China to India via the Nepal border through bazaar spaces.